By Lisa Berman Sylvestri, MSPT, CLT-LANA

This is a 16-minute read.

Muscle pump activity is crucial to the management of lymphedema. The body’s muscles move restorative substances to nourish the pathways with essential fluid flow.

In this article, I’ll explain how decongestive exercises for lymphedema can help someone manage the symptoms of their lymphedema. I’ll share various exercises that stimulate fluid movement, the science that supports the benefits of these exercises, and safety considerations for people with health challenges.

What is Lymphedema?

Lymphedema is a high-protein fluid accumulation within an area of the body, commonly in an arm or leg. It’s important to understand that this is not just water accumulating in an area, but protein-packed lymphatic fluid that builds up in the vessels due to dysfunction in the lymphatic system.

Lymphedema is usually broken down into primary and secondary causes. Primary lymphedema is due to a congenital or a hereditary problem, and secondary lymphedema is due to a dysfunction or interruption of the lymphatic system. Among the most common causes of secondary lymphedema are surgery, trauma, and radiation, including cancer treatment.

Most commonly there are four stages of lymphedema: stage zero, stage one, stage two, and stage three. As the person progresses through the stages, the lymphedema worsens, and the symptoms become more noticeable.

The earlier a patient begins lymphedema treatment, the more effective the treatment usually is. Even when someone is at stage zero, there has already been some type of trauma to the system, and lymphedema may be starting within the body.

For example, if you’ve had oncology surgery and you have a family history of primary lymphedema, you’re more likely to develop secondary lymphedema. Remain vigilant for mild and minor lymphedema symptoms, starting preventive care at stages zero and one.

How Muscle Pump Activity Benefits Lymphedema

Complete decongestive therapy (CDT) can be combined with light exercise in the earliest stages of lymphedema. When I refer to light exercise, this means walking and other mild to moderate forms of physical activity that are known to enhance physical fitness and overall health and wellness.

Exercise is composed of four main components: aerobic training/activity, resistance training, balance training, and flexibility. It’s essential to include all four aspects in an exercise program for treating lymphedema.

Under a doctor’s supervision, a patient should do enough activity to increase the heart rate and make a difference in the body. Keep in mind that lymph flow is high-protein edema that travels through a very complex network of vessels and nodes to the terminus, or terminal point of the lymphatic system.

The lymphatic system is a completely separate system from our blood circulatory system. However, both work together and come together at the terminus. A backup in one system often results in a backup in the other, and our bodies need both systems in top condition to work efficiently.

The lymph nodes gather in four main areas: the armpits, groin, abdomen, and head/neck. Lymph flow moves to and through the regional lymph nodes. Picture the flow moving from your legs into your lymph nodes in the groin, or from your trunk into the lymph nodes in the armpits.

From there, the lymph flows through the main lymphatic duct towards a terminus. All flow is moving in one direction toward these areas. To understand how it flows, remember that lymphatic flow is mostly passive, which means it happens when we’re not thinking about it or actively trying to impact it.

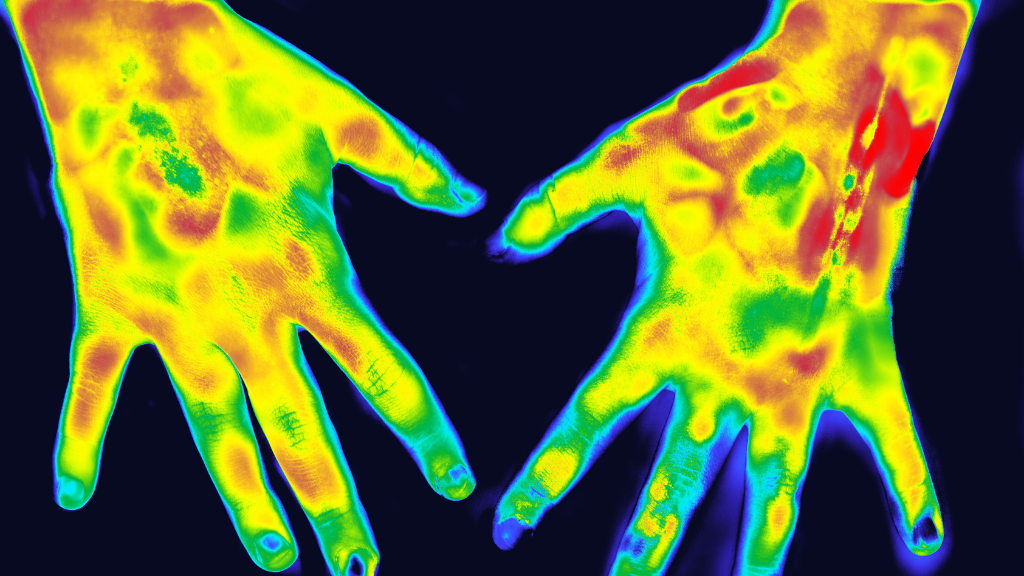

In normal circumstances, lymph movement occurs according to pressure differentials drawing fluid into the lymphatic system. The lymphatic vessels have smooth muscle within them to contract and stimulate flow in one direction. They also have valves that prevent backflow, with nearby arterial and venous pulsation adding to the unidirectional flow.

When lymphedema is present, this flow doesn’t happen normally and vessels begin to fill with fluid. The valves can no longer close appropriately and backflow occurs. (The lymphangion is the section of the vessel between valves.)

This is why the body benefits from exercise during the earliest stages of lymphedema, as well as when the disease is in full progression. Muscle movement promotes an internal pumping activity that increases the pressure on the vessels to promote this unilateral movement, and improved closing of the valves promotes the restoration of proper fluid movement.

Extensive research shows lymphedema patient outcomes improve with exercise. As Melissa B. Aldrich, MBA, PhD, explains, “Published research studies from other research groups of exercise and lymphedema have transitioned in recent years from determining whether carefully prescribed exercise is safe, to showing that it is beneficial.”

Diaphragmatic Breathing for Lymphedema

The first and most important exercise we can do for lymphedema is diaphragmatic breathing. The diaphragm muscle begins at the lower aspect of the rib cage and connects all the way around to our lumbar spine. There are also connections to the pelvic floor that activate during breathing. This is why it’s so important to work on diaphragmatic muscle training to improve the core musculature for smooth lymphatic flow.

When we breathe in, our abdomen expands and our diaphragm goes down and out to increase the space within the abdominal cavity. We exhale, and the diaphragm moves back up and in. It’s this movement, in and out within the abdominal cavity, that creates negative pressure and suction that forces fluid through the thoracic duct and toward the terminus.

When a lymphedema therapist is talking about diaphragmatic breathing, they’re referring to muscle training that directly benefits lymphatic flow. Here’s a diaphragmatic breathing exercise I recommend, which can be done lying down or sitting comfortably:

- Put one hand on your chest and one hand on your abdomen. Start with a few nice, relaxed breaths. Feel your belly moving. Feel the rise and fall of your chest.

- For your next inhalation, focus on breathing in and bringing all the air into your belly. Allow your belly to protrude out as far as you can, then slowly exhale and feel your abdomen go in. Your chest is still going to rise and fall, but I want you to feel the abdomen moving more now.

- Repeat the process several more times. Breathe in, fill the abdomen with air and exhale, then empty all of the air from your abdomen. Feel the breaths becoming more controlled as you hold for an extra second or two for the inhalation and exhalation.

This is something that you can practice every day to strengthen your diaphragm muscle. I recommend this exercise for almost every patient on their initial evaluation and explain why it holds so much benefit for those with progressing lymphedema.

It’s common to feel slightly lightheaded or dizzy when you begin diaphragmatic breathing because you’re processing oxygen slightly differently than you usually do. If you’re feeling this way, stop immediately and return to normal breathing. Later, you can try again slowly over time, and the more you train your body, the less dizziness you will experience.

Research-Backed Benefits of Exercise for Lymphedema

The overwhelming body of research about exercise and lymphedema is related to breast cancer research. For example, Dr. Kathryn H. Schmitz and her team conducted a randomized trial that included over 300 breast cancer patient participants. These patients had two or more lymph nodes removed and followed a 12-week exercise program of supervised exercise routines including aerobic, strength, and flexibility training of about one hour per session.

The researchers found that for patients with a risk of lymphedema, strength training did not increase the risk of getting lymphedema in an affected arm. They also found that a slow progressive weight training regimen resulted in a decreased incidence of exacerbations for those patients who had lymphedema. Patients also had overall reduced symptoms of heaviness and discomfort.

These patients also showed increased strength. This is notable because traditionally, postsurgical breast cancer patients were told to never lift more than five pounds. This study changed the medical community’s perspective on exercise and strength training for people with breast cancer-related lymphedema.

Another key study looked at the immediate effects of active exercise with compression therapy on lower limb lymphedema. In this study, patients performed 15 minutes of exercise on a bicycle or recumbent bike with either a high load, low load, or sitting at rest.

Each bout of exercise was separated by what the researchers called a washout period, which was one week of no activity whatsoever beyond the normal daily routine. In addition to the exercise, which was at 5% to 10% of their normal exertion for 15 minutes, the patients used compression bandages at 40 millimeters of mercury (mmHg).

The researchers found that fluid volume decreased significantly in all three types of interventions. The volume was at the best reduction with active compression and active exercise/compression.

In another study that involved gynecological cancer, the control group of patients only received standard complete decongestive therapy. The CDT was 40 minutes of manual lymph drainage (MLD) with bandaging.

The other group, the exercise group, also performed basic bed exercises of leg lifts and range of motion exercises including ankle exercises. When they became ambulatory, they added to their exercise by walking with no machines or leg weights and just bodyweight exercises.

The study’s researchers concluded that early prevention combined with rehab exercises could reduce the incidence of lower limb lymphedema significantly and improve patients’ quality of life. There was also a notable reduction in cancer-related fatigue, which is a common problem for oncology patients.

These three decongestive exercises for lymphedema studies show the benefits of low-impact forms of exercise like walking and lower limb movement. There’s also significant value in using aquatic exercise to manage the impact of lymphedema.

A 2016 study found that 16 patients with chronic venous insufficiency reported positive impacts from water exercise versus dry land. Patients saw significantly reduced leg swelling and lower limb volume. They also felt better overall and could walk better in their daily lives.

Aquatic exercise isn’t just about moving your body to engage in muscle-pumping action. It’s also about experiencing water pressure and benefiting from its positive effects on the body. Water exerts a pressure of 22.4 mmHg per foot of water depth. When someone is in water four feet deep, the deepest foot-level zone has a pressure of 89 mmHg.

Patients with lymphedema might think they can only tolerate a garment with a pressure of 30, 40, or 50 mmHg. However, they may be intrigued to discover that swimming pool water exerts far more pressure on their lower limbs.

The more pressure you can tolerate, the better you can control your lymphedema. Your muscles are exerting effort to press on the water and feel it pressing back, which is part of the secret to building muscle pumping effectiveness through aquatic exercise.

In Summary: Exercise is for Everyone

I never let a patient tell me, “I can’t exercise.” There is some form of decongestive exercise for lymphedema that’s right for everyone, including those with very limited mobility. If you can’t do anything else, start by raising your heels off the bed. If you can’t even do that, just raise your toes.

Start small and progress slowly. Every bit of exercise, even just 10 minutes here and there, matters when it comes to stimulating lymphatic fluid flow. The more you train your muscles, the more successful you will be at living and thriving with lymphedema.

About the Author

Lisa Berman Sylvestri, MSPT, CLT-LANA, has more than 20 years of experience working in the lymphedema physical therapy field. She holds advanced certification through the Lymphology Association of North America (LANA) and is an educator who teaches physical and occupational therapists about identifying and treating lymphedema. She also plays an important role in her local cancer support community as a guest speaker for newly diagnosed breast cancer patients. She is the founder of Oasis Physical Therapy and Wellness in San Ramon, California.

About Lympha Press

Lympha Press improves lymphatic flow within the body. Clinicians treating lymphedema, lipedema, chronic venous insufficiency, and chronic wounds should consider Lympha Press therapy options for their patients. Lympha Press at-home therapy is easy to use and offers significant relief with results backed by clinical studies.

REFERENCES

- Becker, Bruce. (2009). Aquatic Therapy: Scientific Foundations and Clinical Rehabilitation Applications. PM & R : the journal of injury, function, and rehabilitation. 1. 859-72. 10.1016/j.pmrj.2009.05.017.

- Fukushima T, Tsuji T, Sano Y, Miyata C, Kamisako M, Hohri H, Yoshimura C, Asakura M, Okitsu T, Muraoka K, Liu M. Immediate effects of active exercise with compression therapy on lower-limb lymphedema. Support Care Cancer. 2017 Aug;25(8):2603-2610. doi: 10.1007/s00520-017-3671-2. Epub 2017 Apr 6. PMID: 28386788; PMCID: PMC5486768.

- Gianesini S, Tessari M, Bacciglieri P, et al. A specifically designed aquatic exercise protocol to reduce chronic lower limb edema. Phlebology. 2017;32(9):594-600. doi:10.1177/0268355516673539

- Scallan JP, Zawieja SD, Castorena-Gonzalez JA, Davis MJ. Lymphatic pumping: mechanics, mechanisms and malfunction. J Physiol. 2016 Oct 15;594(20):5749-5768. doi: 10.1113/JP272088. Epub 2016 Aug 2. PMID: 27219461; PMCID: PMC5063934.

- Schmitz KH, Troxel AB, Cheville A, Grant LL, Bryan CJ, Gross CR, Lytle LA, Ahmed RL. Physical Activity and Lymphedema (the PAL trial): assessing the safety of progressive strength training in breast cancer survivors. Contemp Clin Trials. 2009 May;30(3):233-45. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2009.01.001. Epub 2009 Jan 8. PMID: 19171204; PMCID: PMC2730488.

- Wu X, Liu Y, Zhu D, Wang F, Ji J, Yan H. Early prevention of complex decongestive therapy and rehabilitation exercise for prevention of lower extremity lymphedema after operation of gynecologic cancer. Asian J Surg. 2021 Jan;44(1):111-115. doi: 10.1016/j.asjsur.2020.03.022. Epub 2020 May 10. PMID: 32402630.